“During a routine A-12 training flight on 5 January 1967, a fuel gauge failed to function properly, and the aircraft ran out of fuel only minutes before landing. The pilot, Walter Ray, ejected but was killed when he was unable to separate from the ejection seat before impact. The aircraft was completely destroyed. Its wreckage was found on January 6, and Ray’s body was recovered a day later.”

CIA website

January 5, 2025 — Walter R. Ray was an experienced CIA test pilot renowned for his work with the A-12 Oxcart, a top-secret reconnaissance aircraft developed during the Cold War. Ray lost his life on January 5, 1967, when his A-12 experienced a fuel system failure during a test flight near Groom Lake, Nevada. Although he ejected successfully, his parachute malfunctioned, leading to his untimely death. Follow us on Twitter: @Intel_Today

RELATED POST : “Silent Stars: The Fallen Heroes of the CIA” — Book Review by ChatGPT

RELATED POST : Intel Today Book on CIA Memorial Wall Banned by Amazon

Walter Ray, at just 33 years old, was a highly experienced pilot with a long military background. Of his 3,354 hours of flight time, 358 were in A-12s. He had joined the OXCART project on November 7, 1962.

Last Mission

On January 5, 1967, Area 51 (Groom Lake, Nevada) was cold and windy, with snow threatening the nearby mountains. Walter Ray took off just before noon for a four-hour flight to Florida and back.

“The first aerial refueling, immediately after takeoff, was normal, with 928 taking on 36,000 pounds of fuel. After climbing and executing a Mach 3.1 cruise for a while, Ray descended for his second aerial refueling. He took on another 61,000 pounds of fuel, which was 4 to 5,000 pounds less than he was supposed to get, as the tanker had insufficient fuel. Ray was planning to mitigate this fuel shortage by executing a fuel-saving, reduced power climb on the next outbound leg.” [Roadrunners Internationale – CIA Pilot Walter Ray]

By 3:22 pm, Ray noticed a troubling drop in fuel: “I don’t know where my fuel’s gone to,” he reported, observing he was down to 7,500 pounds of fuel instead of the expected 13,000 pounds.

By 3:52 pm, as he descended near Hanksville, Utah, Ray declared an emergency, reporting that he was critically low on fuel. A minute later, the low-pressure lights for the fuel tank began to flash, and shortly afterward, the A-12’s jet engines flamed out.

At 4:03 pm, just ten minutes away from what should have been a safe landing, Ray radioed that he was preparing to eject.

Search and Rescue

The search for Ray began immediately. The next day, at 3:25 pm, a rescue helicopter located the aircraft. They quickly determined that Ray’s ejection had been successful.

However, two days later, they discovered Ray’s body. His ejection seat had failed to separate, preventing his parachute from deploying. As a cover story, the Air Force publicly stated that an SR-71 Blackbird, flying out of Edwards Air Force Base, had crashed.

Official Accident Report

The official accident report attributed the crash to a malfunctioning fuel quantity gauge. In his radio transmission before ejecting, Ray reported:

“I have a loss of fuel and I do not know where it is going; I think I can make it [to Groom Lake].”

CIA pilot Walter L. Ray was ultimately forced to eject. Tragically, the ejection seat’s separation sequence, which was designed to occur at 5 km, malfunctioned. Ray was killed on impact with the ground, still strapped to his seat.

The automatic system, intended to separate the pilot from the seat — even if the pilot was unconscious — was clearly defective.

Ray was not wearing his custom-fitted pressure suit, but one that was larger. This may have contributed to the fatal outcome, as it could have hindered his ability to survive the ejection and fall.

Ejection from the A-12

After ejecting from the A-12, the pilot remained strapped into the seat, which deployed a small drogue parachute to slow and stabilize the descent.

Upon reaching a much lower, preset altitude, the seat was designed to automatically release the straps, and the pilot would be forcibly ejected from the seat by the tightening of “butt-snapper” straps — located under the pilot’s seat, they pushed him upward and out, hence the name.

Afterward, the pilot’s parachute would open automatically, allowing him to complete the descent. This system was well-designed, intended to safely recover pilots from extremely high altitudes, even if they were injured or unconscious.

Ray, who was relatively short, had his seat’s headrest modified and extended downward to ensure a proper fit. His parachute backpack may have jammed under the seat’s headrest.

Another potential contributing factor to the malfunction was the installation of screws in the seat, which protruded slightly. Both of these untested modifications were made without supervisory oversight.

Why Ray couldn’t manually free himself remains unclear, as there was no obvious reason he should have been unconscious.

This lack of clarity about his condition adds to the mystery surrounding the incident.

Not the full story

The accident report summary reveals that during the second refueling, Ray received 4,000 to 5,000 pounds less fuel than he was supposed to.

It also notes that during this refueling, the chase aircraft was refueled first and took 4,000 pounds of fuel, which, if available to Ray’s aircraft, might have enabled him to return safely to base.

Muzzling the Media

Marvin Miles, the Aviation Editor for the Los Angeles Times at the time, had been contacting the Public Information Office at Edwards Air Force Base.

Suspecting that something unusual had occurred, Miles planned to publish a story suggesting an “exposure” of the incident. However, the LA Times never published his article, and the story was effectively suppressed.

Funeral Special instructions were issued for those wishing to attend Ray’s funeral in Palmdale. Only close friends were allowed to attend, and no uniforms were permitted. Attendees were instructed not to sign the funeral register.

Furthermore, they were advised to avoid conversations with unrecognized individuals. If questioned about their place of employment, attendees were instructed to simply say “Lockheed.” However, staff from Hughes and Pratt & Whitney were allowed to acknowledge their actual affiliations.

These precautions underscored the secrecy surrounding the OXCART program and the circumstances surrounding Ray’s death.

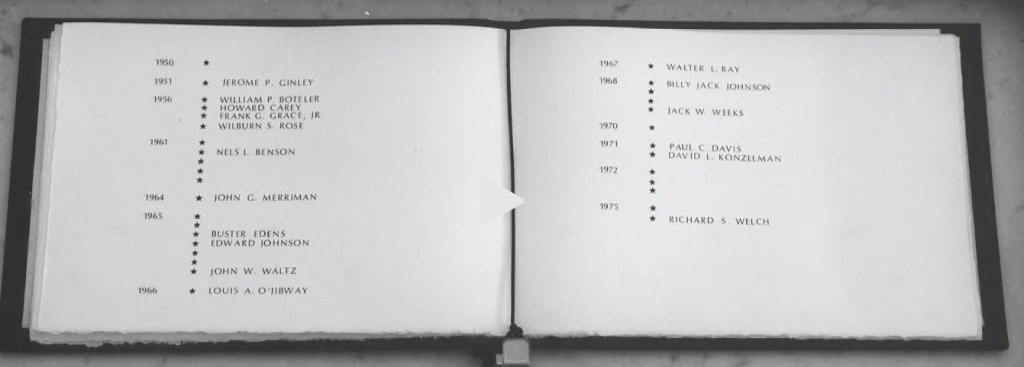

Memorial Wall and Book of Honor

Walter Ray is commemorated with one of the initial stars on the Memorial Wall, and his name was inscribed in the initial Book of Honor.

References

“Piece of Metal from A-12.” CIA website. Thomas P. McLninch.

“The Oxcart Story.” CIA website.

Roadrunners Internationale – CIA Pilot Walter Ray

Lockheed A-12 — Wikipedia

CIA Documentation Concerning Ray’s Crash of the A-12

=

CIA memorial Wall — STAR 21 : Walter R. Ray (Hanksville, Utah – January 5, 1967)