“We must never again keep secret the evolution of our nation’s intelligence agencies from the scrutiny of the Congress or the people.”

Jimmy Carter

1976

Presidential campaign

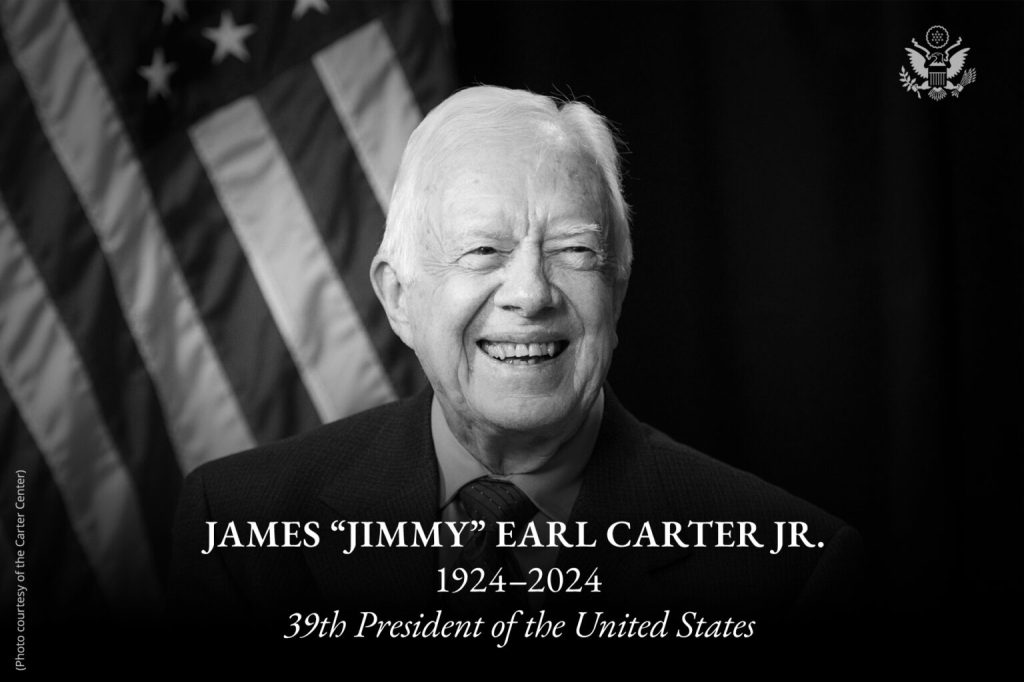

January 3, 2025 — In his Memoirs, Carter reflects on his presidency (1977–1981), including his perspectives on foreign policy and intelligence matters, and his concerns about the conduct of the CIA and the need for reform. Carter was deeply troubled by governmental deception in foreign policy and by the “CIA’s role in plotting murder and other crimes.” Follow us on Twitter: @Intel_Today

RELATED POST : On This Day — President Carter Signs Executive Order 12036 [Ban on Assassination] (January 24 1978)

RELATED POST: One Year Ago — Zbigniew Brzezinski: “An exceptional failure all round.”

RELATED POST : On This Day — Tehran Releases 52 US Hostages After 444 Days (January 20 1981)

In his commencement address at the University of Notre Dame on May 22, 1977, President Jimmy Carter stated, “For too many years, we’ve been willing to adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries, sometimes abandoning our own values for theirs,” outlining his vision for a foreign policy grounded in American values and human rights.

In the context of the Cold War and the aftermath of the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal, Carter’s remarks called for a return to ethical foreign policy based on democratic principles. His call for a foreign policy rooted in American values was quickly followed by concrete action.

Executive Order 12036 – Ban on political assassination

In line with his commitment to ethics and human rights, Carter signed Executive Order 12036 on January 24, 1978, which prohibited U.S. intelligence agencies from engaging in political assassinations.

The key section of the order stated: “No employee of the United States Government shall engage in, or conspire to engage in, political assassination.”

This ban on political assassination was a direct response to the revelations of the Church Committee, which had uncovered widespread abuses by U.S. intelligence agencies, including covert operations that violated human rights and democratic principles.

Carter’s executive order was part of broader reforms to improve oversight and accountability within the intelligence community, ensuring that such practices would not continue.

“One can assess a prince’s intelligence by looking at the men with whom he surrounds himself.”

The Prince

Niccolò Machiavelli

Italian Renaissance political philosopher

This observation underscores the idea that a leader’s choice of advisors and associates is a reflection of their own judgment and values. Machiavelli suggests that the competence and character of a leader’s inner circle can reveal much about the leader’s qualities and decision-making abilities.

This perspective aligns with modern leadership theories, which emphasize the importance of surrounding oneself with capable and trustworthy individuals to enhance decision-making and organizational success.

In matters of intelligence and foreign policy, President Jimmy Carter surrounded himself with key figures such as Vice President Walter Mondale, Director of Central Intelligence Stansfield Turner, and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Each played a significant role in shaping Carter’s approach to governance, especially in navigating complex global challenges.

“Almost anything bad that happens in the world is attributed to the CIA.”

Vice President Walter Mondale

Reorganizing the CIA

Foreign policy (1976)

Walter Mondale – A Highly Principled Vice President

During the 1976 U.S. presidential campaign, Walter Mondale, running for vice president alongside Jimmy Carter, made strong statements about the CIA, criticizing its actions and the broader intelligence community.

In a 1976 campaign speech, Mondale suggested that the CIA had been involved in activities that were damaging to both American values and its global reputation. In one famous statement, he remarked that the CIA had brought “disgrace” to the United States due to its covert operations and involvement in controversial activities such as coups, assassination plots, and surveillance of American citizens.

This critique aligned with broader criticism of the intelligence community, particularly after the revelations from the Church Committee, which investigated abuses by the CIA, FBI, and NSA in the mid-1970s.

Mondale’s comments were part of a broader critique of U.S. intelligence practices. Together with Carter’s call for reform, they were central to the campaign’s emphasis on restoring American ethics and values in foreign policy.

“We can’t use them if they’re a bit stupid.”

DCI Stansfield Turner,

about dismissing 800 CIA employees

Halloween Massacre (1977)

New CIA Director: Stansfield Turner

When Jimmy Carter became president in 1977, he chose not to retain George H.W. Bush as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI).

Bush had been appointed to the position by President Gerald Ford in 1976, but Carter sought a leader who aligned more closely with his vision of reforming the intelligence community.

He appointed Admiral Stansfield Turner as the new DCI. Turner shared Carter’s goal of restructuring the CIA, focusing on greater oversight, ethical constraints, and reducing the agency’s reliance on clandestine operations.

Turner was particularly alarmed by the CIA’s troubling history, which included its involvement in political assassinations, covert coups, and other clandestine actions that often contradicted American democratic values. These practices, remnants of Cold War-era policies, were viewed as deeply unethical by the Carter administration.

Turner’s most disturbing discovery was the harsh questioning and illegal imprisonment the CIA imposed on Soviet defector Yuri Nosenko, who had been held and tortured for years by the CIA’s Counterintelligence Staff. This story convinced Turner that the CIA was a dangerous place if left unchecked. This case, in particular, underscored the need for stringent oversight and accountability.

Further fueling Turner’s concerns was the discovery—based on information from Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward—that former CIA officer Edmund Wilson had worked for Libyan President Muammar Qaddafi and maintained contacts within the CIA. This raised doubts about the probity and security of the Directorate of Operations (DO), which was responsible for the CIA’s covert actions.

In response to these revelations, Turner took decisive action. He initiated significant personnel reductions within the CIA, including the controversial firing of several hundred employees, a move that became known as the “Halloween Massacre.” This restructuring was designed to streamline the agency and reduce its focus on covert operations, aligning its priorities more closely with intelligence analysis and less on clandestine interventions.

Turner’s tenure as DCI was marked by his determination to bring the CIA into alignment with American values, ensuring that it operated with the transparency and accountability necessary to rebuild public trust. His reforms, while controversial, reflected a critical shift toward a more ethical and oversight-driven intelligence community.

“President Carter understood that good intelligence — delivered with honesty and integrity — was the foundation of good policy.”

William J. Burns

December 29, 2024

Many analysts and former CIA officials have noted that during President Jimmy Carter’s administration, there was confusion within the CIA regarding his expectations.

According to a 2009 piece [“The CIA and the Culture of Secrecy”] published by The New York Times:

“For many at the CIA, it was unclear whether they were expected to carry out their usual operations, or whether the Carter administration was asking them to abandon practices that had defined the Agency’s work for decades.”

Carter’s foreign policy was characterized by a commitment to human rights, ethical standards, and transparency, which were sometimes at odds with the traditional covert operations of the CIA.

Admiral Stansfield Turner, Director of Central Intelligence (1977-1981), made it very clear what Carter demanded and expected from the CIA.

“The CIA had grown up in a world of secrecy and covert operations. Carter wanted to create a new culture, one where transparency, accountability, and ethics would guide our actions.”

In simple terms, Carter wanted the CIA to operate with competence and honor. He had little patience for those within the agency who failed to align with this vision, which ultimately led to the infamous Halloween Massacre.

Critics have often dismissed him as naive, portraying him as an idealist with an overly innocent view of the world. However, nothing could be further from the truth. Carter understood all too well that the world is a harsh and complex place.

His insistence on accountability and ethics in the CIA was not born of naivety but of a keen awareness that a lack of such principles invariably leads to disastrous outcomes. The debacle surrounding the SALT II Treaty serves as a stark example of this point.

“As long as the two nuclear superpowers maintain arsenals in the tens of thousands of nuclear warheads, there is no way they can with any consistency urge that other nations not be allowed to acquire these weapons.”

DCI Stanley Turner

CIA Political Interference and Repercussions on the SALT 2 Treaty

The SALT II Treaty (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks II) was a landmark agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union, designed to limit the number of nuclear weapons each side could maintain.

Signed in June 1979 by U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev during a ceremony in Vienna, the treaty represented a significant step toward arms control during the Cold War.

However, the treaty was never ratified, a failure that can be directly traced to the CIA’s shortcomings in both Australia and Iran. These intelligence failures undermined U.S. credibility, strained international alliances, and complicated the diplomatic landscape, contributing to the collapse of support for the treaty.

The CIA’s alleged involvement in the 1975 dismissal of Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam created tensions in U.S.-Australia relations and fueled skepticism about U.S. activities in Australia.

This controversy contributed to the disillusionment of CIA contractor Christopher Boyce, who became deeply critical of the agency’s perceived undermining of democracy. In response, Boyce leaked sensitive information about U.S. operations at the Pine Gap listening facilities to the Soviet Union.

Armed with insights into America’s monitoring capabilities, the Soviets adapted their strategies to evade or mislead these systems, significantly weakening the U.S.’s ability to gather reliable intelligence.

The CIA’s failures in this case—including its inability to detect Boyce’s betrayal and its unethical actions in Australia—had a profound and costly impact on the U.S. intelligence community.

Around this time, significant political upheaval was unfolding in Iran. On January 16, 1979, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was forced to flee the country amidst widespread protests and unrest.

Just weeks later, on February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned to Iran after more than 14 years in exile, leading to the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This revolution marked a dramatic shift in the Middle East and remains one of the defining moments of 20th-century history.

Despite mounting evidence of these developments, the CIA failed to anticipate the events in Iran, a lapse that has been heavily criticized. One major consequence of this intelligence failure was the loss of two vital U.S. listening stations in Iran, TACKMAN I and II, which were crucial for monitoring the Soviet launch site at Tyuratam (now the Baikonur Cosmodrome). These stations were integral to the U.S. intelligence network during the Cold War, particularly for tracking Soviet missile tests.

The weakening of the Pine Gap facilities, combined with the loss of both listening stations in Iran, severely undermined the United States’ ability to verify the terms of the treaty. Coupled with a shifting political climate, these setbacks further eroded support for the agreement.

As a result, the treaty was never formally ratified, exacerbating tensions and fueling the continued escalation of the Cold War. By January 1980, President Carter was forced to abandon efforts to secure ratification of the SALT II Treaty in the U.S. Senate.

“Ronald Reagan made a deal with the Iranians about the hostages release before he was elected.”

Alan Dershowitz

Harvard Law Professor

(February 2017)

The Iran hostage crisis

On January 20, 1981, just 20 minutes after President Ronald Reagan concluded his inaugural address, the Islamic Republic of Iran announced the release of 52 Americans who had been held hostage since November 4, 1979.

Allegations that the Reagan campaign negotiated a delay in the release of the hostages until after the 1980 presidential election have been widely discussed.

Gary Sick, a principal White House aide for Iran and the Persian Gulf on the Carter and Reagan administrations’ National Security Council, concluded that CIA Director William Casey and George H. W. Bush had indeed negotiated such a delay.

Sick claimed, “Mr. Karrubi agreed in the second Madrid meeting to cooperate with the Reagan campaign about the timing of any hostage release. In return, he was promised that the Reagan administration, once in office, would return Iran’s frozen assets and help them acquire badly needed military equipment.”

Barbara Honegger, who worked for the Reagan administration, later stated that she had uncovered information suggesting that George H. W. Bush and William Casey conspired to ensure Iran would not release the U.S. hostages until after President Jimmy Carter had been defeated in the 1980 election. She alleged that arms sales to Iran were part of the arrangement.

In 1987, during the Iran-Contra investigations, Honegger reported that shortly after October 22, 1980—when Iran abruptly changed the terms of its negotiations with Carter—a Reagan campaign insider remarked to her, “We don’t have to worry about an October surprise. Dick (referring to Richard V. Allen) cut a deal.”

In March 2023, Ben Barnes, a prominent Texas politician, revealed that former Texas governor John B. Connally Jr. had initiated contact with Iran during a trip to the Middle East in the summer of 1980.

According to Barnes, Connally kept both Reagan and Casey updated on his progress. Connally departed Houston on July 18, 1980, visiting Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel before returning on August 11. He reportedly delivered the same message to his contacts in each country:

“Look, Ronald Reagan’s going to be elected president, and you need to get the word to Iran that they’re going to make a better deal with Reagan than they are with Carter. It would be very smart for you to pass the word to the Iranians to wait until after this general election is over.”

The Reagan administration later rewarded Iran for its cooperation by supplying weapons via Israel and unblocking Iranian monetary assets frozen in U.S. banks.

During his research, Gary Sick spoke with several former hostages. One response, in particular, deeply moved him. After hearing the evidence, the former hostage said, “I don’t want to believe it. It’s too painful to think about it.”

This story, often described as one of the greatest betrayals in modern U.S. history, remains deeply painful to consider. Unfortunately, the American public has largely lacked the will to confront this event honestly—a moment that profoundly altered the course of history for the worse.

“If we had gotten the hostages home, we’d have won, I really believe that. It’s pretty damn outrageous.”

Gerald Rafshoon

Carter’s White House communications director

Did the CIA betrayed US President Jimmy Carter?

For several reasons, Jimmy Carter was highly unpopular within the CIA, an agency where his predecessor, George H. W. Bush, had been a widely admired Director of Central Intelligence (DCI).

Carter’s decision to dismiss Bush as DCI and the subsequent “Halloween Massacre,” which saw hundreds of CIA personnel removed from their positions, undoubtedly created a powerful group of adversaries for the president.

These individuals had spent their careers mastering the arts of staging coups and interfering in elections around the world. When suddenly left without their roles or influence, one might ask: What were they likely to do next? The reader is free to draw their own conclusions, but one additional detail is worth noting.

William Casey, who replaced Stansfield Turner as CIA Director during the Reagan administration, managed to “surreptitiously” obtain a Carter campaign briefing book before the lone debate between Carter and Reagan in the 1980 presidential race. How did this happen?

References

“Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President” (1982). p 143

A Four-Decade Secret: One Man’s Story of Sabotaging Carter’s Re-election — NYT (March 18, 2023)

INNOCENCE ABROAD: JIMMY CARTER’S FOUR MISCONCEPTIONS — Reader’s Digest (May 1980)

Statement by William J. Burns on Passing of President Jimmy Carter — CIA Website

President Carter: The White House Years

Stuart E. Eizenstat (Thomas Dunne Books, 2018), 898 pp., notes, index.

Reviewed by Thomas G. Coffey

=

Did the CIA betray President Jimmy Carter ?