“The very word ‘secrecy’ is repugnant in a free and open society; and we are as a people inherently and historically opposed to secret societies, to secret oaths and to secret proceedings.”

President John F. Kennedy

Waldorf-Astoria Hotel

New York City

April 27, 1961

March 5 2024 — Kennedy, like many other leaders before him, recognized the need for certain levels of confidentiality in matters of national security. Yet, the tension between the imperatives of national security and the principles of transparency remains a complex aspect of governance. Follow us on Twitter: @INTEL_TODAY

“How should we view all of this [spying] activity? It is a distasteful but vital necessity.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower

News conference following Soviet downing American reconnaissance aircraft

May 11, 1960

While acknowledging the distasteful nature of espionage, President Eisenhower understood that in a world marked by ideological and political rivalries, intelligence gathering was a necessary tool for protecting national interests and ensuring the security of the nation.

This perspective underscores the complex and often morally ambiguous nature of intelligence work in the context of global geopolitics.

While it’s acknowledged that some level of secrecy may be necessary for matters of national security, diplomacy, and personal privacy, finding the right balance between the need for transparency and the protection of sensitive information is a continuous challenge in democratic governance.

Striking this balance is essential to ensure that a government remains accountable, responsive, and true to the democratic values it represents.

The statement that “unnecessary secrecy is a threat to democracy” reflects a commonly held perspective among advocates of open government and transparency.

Here are the reasons put forward to explain why unnecessary secrecy can be a potential threat to democracy:

— Lack of Accountability: Excessive secrecy can hinder accountability by shielding decision-making processes and actions from public scrutiny. In a democratic system, accountability is crucial for maintaining the trust of the citizens in their government.

— Violation of Democratic Principles: Democracy is built on the principles of transparency, participation, and the rule of law. Unnecessary secrecy can undermine these principles and erode the foundations of a democratic society.

— Potential for Abuse of Power: Secrecy provides an environment where abuses of power can occur without proper oversight. Leaders and institutions may engage in actions that are contrary to the public interest when shielded from scrutiny.

— Informed Citizenry: In a democracy, an informed citizenry is essential for making meaningful decisions at the ballot box. Excessive secrecy limits access to information, making it challenging for citizens to make informed choices about their leaders and policies.

— Stifling Public Debate: Open and honest debate is vital for a healthy democracy. Secrecy can stifle public discourse by preventing citizens from having access to the information necessary for meaningful discussions on important issues.

— Trust Erosion: A lack of transparency can lead to a erosion of trust between the government and its citizens. Trust is a fundamental component of a successful democratic system, and unnecessary secrecy can contribute to its breakdown.

While I wholeheartedly concur with the aforementioned points, I would like to highlight an infrequently discussed factor. The quality of work conducted under conditions of secrecy is consistently compromised.

Without an equivalent to a peer-review system and the inability of experts to rectify errors in clandestine operations, mistakes persist and frequently propagate additional inaccuracies. Over time, the perspectives maintained by secretive organizations often become disconnected from reality.

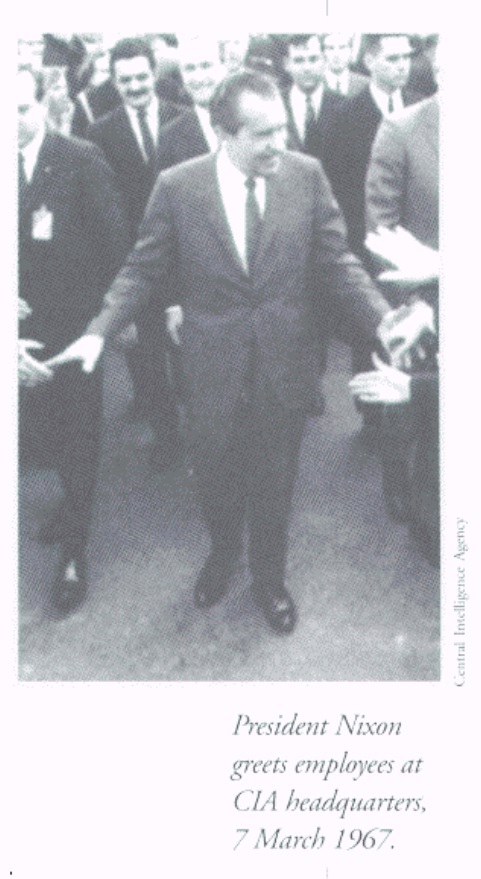

Not convinced? Consider the picture of Nixon visiting the CIA above, sourced from a CIA publication titled ‘Our First Line of Defense: Presidential Reflections on US Intelligence.’

The caption reads: ‘President Nixon greets employees at CIA headquarters, 7 March 1967.’

Richard Nixon, serving as the 37th President of the United States, commenced his presidency on January 20, 1969, and resigned on August 9, 1974, in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal. A curious mistake arises here – President Nixon visited the CIA headquarters only once, delivering a speech to agency employees on March 7, 1969.

However, the caption inaccurately places this event in 1967, a time when Nixon was not even president. The discrepancy in the date serves as a vivid example of the importance of accuracy and transparency in historical records.

Perhaps, the reader will argue that this example is not an important mistake. I will remind you the wise words of Albert Einstein: “Whoever is careless with the truth in small matters cannot be trusted with important matters.”

Robert Oppenheimer made the same point when he stated: “Our own political life is predicated on openness. We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to enquire. We know that the wages of secrecy are corruption. We know that in secrecy error, undetected, will flourish and subvert.”

In a recent article, William J. Burns, the current Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, highlighted that ‘trust in the United States’ public institutions is often in short supply.’ (Foreign Affairs: ‘Spycraft and Statecraft — Transforming the CIA for an Age of Competition’ by William J. Burns, March/April 2024).

Indeed, government agency ratings remain largely negative. Gallup’s periodic assessments of Americans’ opinions on various federal agencies and departments reveal that most current ratings are at or below trend averages, with nine of the 16 agencies at or near their lowest points in the trend.

Despite minimal changes in agency ratings over the past year, there is a notable six-percentage-point decrease in Americans’ rating of the CIA.

Perhaps, as Director Burns examines these trends, he should consider the impact of over-secrecy on fostering suspicions.

The connection between transparency, public trust, and agency ratings underscores the ongoing challenge of striking the right balance between the necessity for secrecy and the imperative of openness in a democratic society.

REFERENCES

“Our First Line of Defense: Presidential Reflections on US Intelligence.” — CIA publication

Image: White House Photo Office: WHPO-0465-29A — Richard Helms, seen here directly behind the President, served as the Director of Central Intelligence 1966-1973.

Robert Oppenheimer, as mentioned in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (1951)

=

On the necessary evil of secrecy

“When even one American – who has done nothing wrong – is forced by fear to shut his mind and close his mouth, then all Americans are in peril.”

President Harry S. Truman